For decades, Chhattisgarh has been spoken about in the language of extraction and conflict with mines, forests, and Naxal violence dominating headlines. What remained largely absent was another truth: that this land was also among the earliest theatres of resistance against colonial rule, led by tribal communities whose courage rarely entered history textbooks.

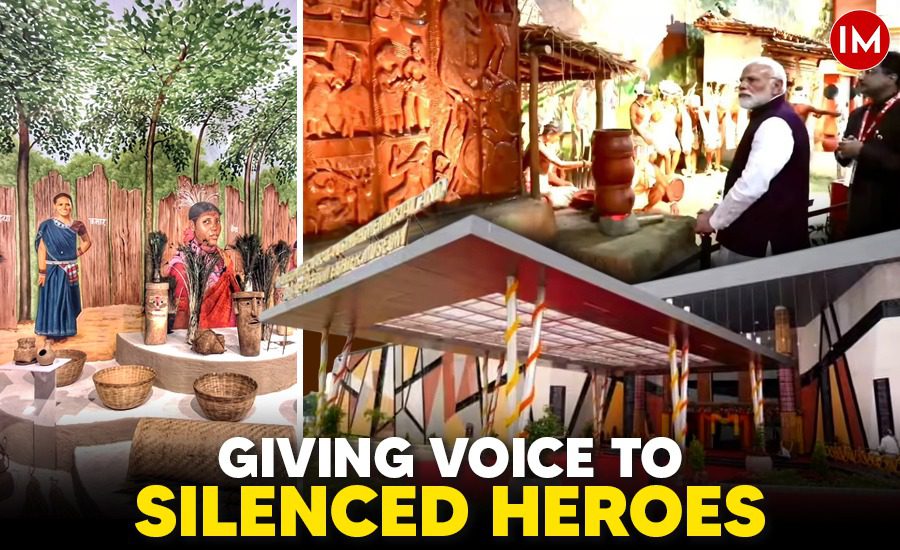

In Nava Raipur, that silence has been broken, visually, spatially and emotionally, through the Shaheed Veer Narayan Singh Memorial and Tribal Freedom Fighters’ Museum, India’s first digital tribal museum. Behind its conception, speed of execution and narrative clarity stands Sonmoni Borah, a 1999 batch IAS officer of Chhattisgarh cadre and the Principal Secretary of Chhattisgarh’s Tribal Welfare Department, who led the project from the front.

Completed in record time under his supervision, alongside the state’s first tribal museum, the freedom fighters’ museum is not merely an institution. It is a reordering of memory.

“This museum is about restoring voice and dignity to histories that were pushed to the margins for centuries. We wanted visitors to feel the struggle, not just read about it,” Borah shared with Indian Masterminds.

A MUSEUM THAT BEGINS WITH A TREE

Spread across 9.75 acres and built at a cost of ₹53.13 crore, the museum was inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on November 1, marking Chhattisgarh’s foundation day and 25 years of statehood. It is a joint initiative of the Union Ministry of Tribal Affairs and the Chhattisgarh government.

The first encounter inside the museum sets the tone. Visitors are greeted by a striking installation of a tree – its form blending saja, sal and mahua, species central to tribal life. Behind it hang symbols once used for covert resistance: a clenched fist holding a mango twig to summon a gathering; the same fist with chillies to signal decision-making; and finally, the addition of an arrow, a call for armed resistance.

These visual codes, once whispered across forests, now stand illuminated in a public space.

“We were very clear that the museum’s language should come from within tribal culture, not be imposed from outside,” Borah explains. “Every symbol here has meaning rooted in lived practice.”

SIXTEEN GALLERIES, CENTURIES OF RESISTANCE

The museum unfolds through 16 immersive galleries, housing nearly 650 sculptures, digital installations and audio-visual narratives. The journey begins with everyday tribal life with life-size figures dancing, beating drums, tending animals, farming, cooking, before gradually darkening into the arrival of Maratha and British rule.

From 1774 to 1939, visitors are taken through stories of exploitation, forced taxes, forest restrictions, violence and rebellion. Major uprisings, from the Halba and Sarguja Krantis to the jhanda and jungle satyagrahas, are depicted in sculptural detail.

One arresting installation is the Kaanta Jhula (thorn swing), associated with spiritual possession rituals. Another shows Captain Blunt of the East India Company retreating after tribal resistance blocked his entry into Bastar in 1795.

At the heart of the museum stands Veer Narayan Singh, Chhattisgarh’s first freedom fighter and a leader of the 1857 rebellion, who rose against British authorities when they refused grain to starving tribals. His story anchors the narrative, but it does not stand alone.

The galleries honour leaders such as Gaind Singh, Gundadhur and Ramadhin Gond, while the entrance proudly displays the names of 200 tribal freedom fighters, carved into wood sourced from the Sarguja region.

“This is not about one hero,” Borah says. “It is about a collective history of resistance that shaped this region long before modern politics.”

DIGITAL STORYTELLING IN TRIBAL LANGUAGES

What sets the museum apart is its deep integration of technology. Conceived as a fully digital museum, it includes interactive screens, motion-activated displays, immersive domes and a mini-theatre screening short films on tribal leaders and movements.

Under Borah’s leadership, the department worked closely with the Tribal Research and Training Institute (TRTI) to ensure authenticity. Content has been developed in Chhattisgarhi, Gondi, Halbi and other local languages, supported by the ‘Adi Vani’ app, which enables translation and access for tribal visitors.

“We didn’t want technology to overwhelm the story,” Borah notes. “The idea was to use digital tools to make history accessible, especially to young people from tribal communities.”

Plans are underway for an amphitheatre, expanding the museum into a living cultural space rather than a static exhibition.

BEYOND STEREOTYPES, TOWARDS IDENTITY

Nearly 31 per cent of Chhattisgarh’s population belongs to tribal communities. For Chief Minister Vishnu Deo Sai, the museum fits into a larger effort to reshape how the state understands itself, through initiatives like PM JANMAN and the Dharti Aaba Abhiyan, curriculum updates and national cultural platforms.

In a region long associated with conflict, the museum carries a different message.

“At a time when development is reaching even our remote villages and Naxal influence has sharply declined, institutions like this hold special meaning,” Sai has said. “They help people reconnect with their heritage and draw strength from the sacrifices of their ancestors.”

Borah echoes this sentiment but grounds it in administration. “Development and culture are not competing ideas,” he says. “If people know who they are and where they come from, governance becomes more meaningful.”

BUILDING AT SPEED, LEADING FROM THE FRONT

What makes the project remarkable is not only its ambition, but its pace. The museum was completed within months of the state’s first tribal museum opening, both executed under Borah’s direct supervision.

From curatorial decisions and architectural planning to coordination with the Centre, artists, historians and digital teams, Borah remained closely involved. Even practical challenges, such as the museum’s distance from Raipur city, are being addressed, with plans for improved public transport access, including a dedicated bus stop.

“This was built in record time because everyone involved believed in its purpose,” Borah told Indian Masterminds. “My role was to ensure clarity, coordination and momentum.”

MEMORY AS PUBLIC INFRASTRUCTURE

As visitors move through dimly lit galleries into open courtyards, where a life-size statue of Birsa Munda stands in quiet dignity, the museum leaves a lasting impression. It does not simplify history, nor does it seek spectacle alone. Instead, it insists on remembrance.

In Nava Raipur, amid government buildings and new roads, the Shaheed Veer Narayan Singh Memorial and Tribal Freedom Fighters’ Museum asserts that progress is also about what a society chooses to remember.

And through Sonmoni Borah’s leadership, those memories, once confined to forests, songs and oral tradition, now stand carved, coded and claimed in the public imagination.