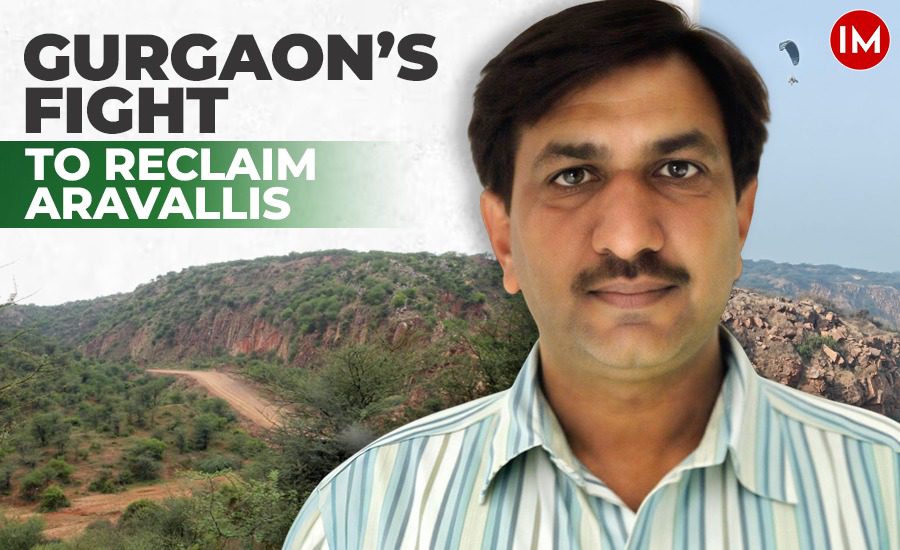

In the rugged folds of the Aravalli hills, land is scarce, rainfall is limited, and ecological mistakes of the past still cast long shadows. As Gurgaon’s Divisional Forest Officer, 2010 batch IFS Subhash Yadav is confronting one of the region’s most complex challenges: undoing decades of ecological damage caused by invasive species and restoring what once thrived naturally.

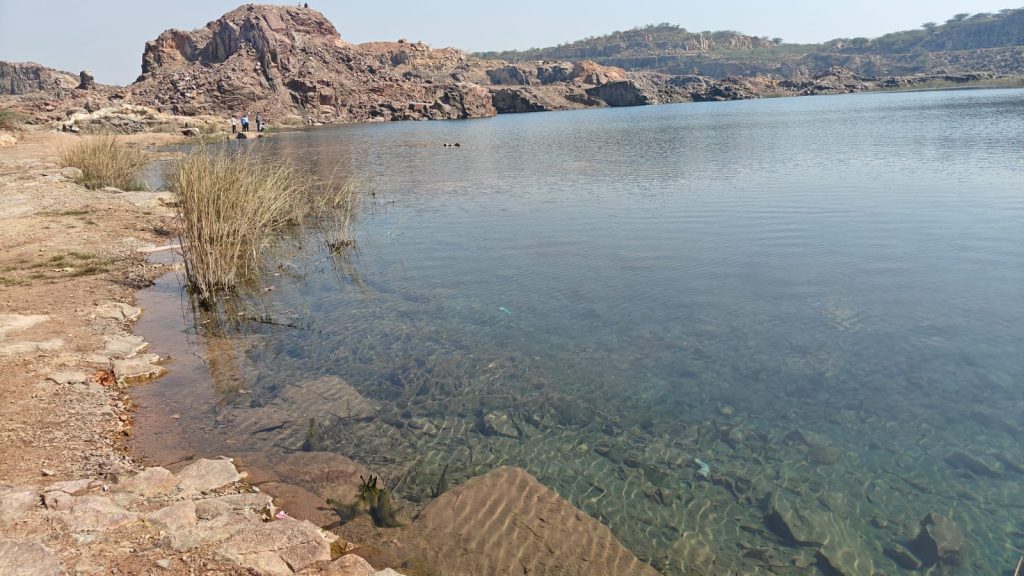

“This is a dry landscape. Annual rainfall is barely around 500 mm. Water bodies survive only for two to three months after the monsoon. Every decision here has to respect that reality,” Mr. Yadav shared in an exclusive conversation with Indian Masterminds.

THE PROBLEM ROOTED IN THE PAST

The Aravallis did not degrade overnight. One of the biggest disruptors has been Prosopis juliflora, commonly known as ‘Vilayati Kikar’, an exotic and invasive species introduced during the 1990s Aravalli project. At the time, the intent appeared practical: to reduce pressure on natural forests by ensuring a steady supply of fuelwood.

But the long-term impact proved severe.

“Once Prosopis establishes itself, nothing grows beneath it,” Yadav says. “It spreads aggressively, wipes out grasslands, and blocks indigenous species completely.”

Grasslands disappeared, biodiversity collapsed, and the ecological chain began to break. First herbivores, then carnivores.

FROM INVASIVE THICKETS TO LIVING FORESTS

The core of the Gurgaon forest division’s current strategy is clear: remove invasive exotics and replace them with indigenous species, while allowing nature to heal gradually.

The first targets are dense Prosopis patches where removal creates ecological “openings.” These spaces will then be seeded and planted with native vegetation. Around 25% of new plantations will include fruit-bearing species, carefully chosen to support birds and wildlife.

“Removal alone is not enough,” Yadav notes. “You have to prepare the land to receive native species again like grasses, shrubs, trees, and everything that belongs here.”

Grasslands, once lost, are being consciously rebuilt because they are the foundation of the food chain in the Aravallis.

WILDLIFE CONFLICT AND THE VANISHING GRASSLANDS

As grasslands vanished, herbivores were pushed out of forest areas and into agricultural fields. Carnivores followed.

“When animals don’t find food inside, they come out,” Yadav explains. “That’s why we see leopards straying into places like Manesar, Faridabad, and Gurgaon. Rescues keep happening, but the root cause lies inside the forest.”

Restoration, in this sense, is not just about trees; it is about keeping wildlife where it belongs, inside functional ecosystems.

CLOSING THE FOREST, HEALING THE LAND

A crucial part of the restoration plan is area closure. Select zones will be protected from biotic interference through boundary walls and village-side barriers. Inside these secured areas, multiple ecological components will work together:

- Seeding and planting of native species

- Restoration of seasonal water bodies

- Creation of water holes for wildlife

- Development of grasslands

- Soil moisture conservation and catchment treatment

- Revival of natural springs

“This landscape once had functioning water catchments,” Yadav told Indian Masterminds. “We are working on spring recharge and catchment treatment so water stays longer and supports both forests and wildlife.”

SCALE, TIMELINES, AND PARTNERSHIPS

Work has already begun on identified sites, including a 1,000-acre patch where invasive removal is underway. The immediate target is to complete substantial work before the monsoon, using rainfall as a natural ally.

In the first phase, 10,000 hectares across four to five districts in Haryana’s south circle have been identified. Field work is expected to intensify around July–August.

The model relies heavily on collaboration with CSR partners, NGOs, public participation, and scientific institutions. Long-term sustainability is built into the plan.

“Our proposals include ten years of maintenance,” Yadav says. “There will be departmental monitoring, third-party evaluation, and oversight linked to compensatory afforestation norms.”

SCIENCE AT THE CORE

Scientific backing strengthens every step. Wildlife monitoring, censuses, and habitat assessments are being conducted with expert institutions to ensure the changes are measurable and real.

This is not cosmetic greening. It is a slow, layered ecological repair.

A DRY FOREST, REIMAGINED

The Aravallis around Gurgaon are fragile, but not beyond recovery. By removing what never belonged, restoring what once existed, and protecting water at its source, the forest division is attempting something rare: bringing balance back to a damaged landscape.

Yadav puts it simply:

“If native plants return, grasslands return. Herbivores return. And when food is available inside, wildlife stays inside. That’s the whole idea.”

In the quiet clearings left behind by invasive thickets, a different Aravalli is beginning to emerge, one shaped not by quick fixes, but by patience, planning, and respect for the land.