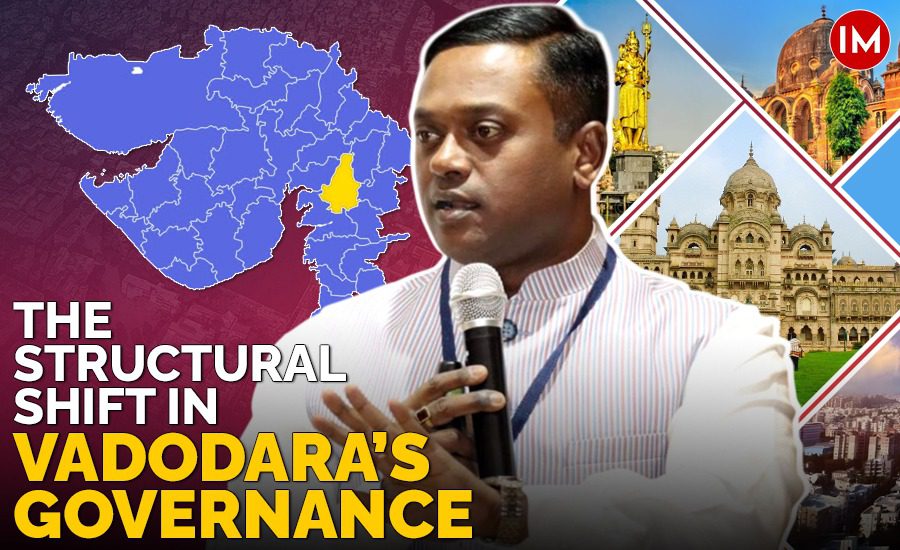

On most mornings, the Khanderao Market building stands as it has for over a century—ornate, dignified, and deeply woven into Vadodara’s civic memory. Built in 1906 under Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III, it has long served as the heart of the city’s municipal administration. But for Arun Mahesh Babu (IAS, 2013 batch, Gujarat cadre), Vadodara’s future cannot be confined within the limits of a 120-year-old structure.

With the presentation of the ₹7,609-crore budget for 2026–27, Babu has not merely tabled financial allocations; he has unveiled a structural reset for Gujarat’s third-largest city. At its core lies a long-pending but transformative decision—the operationalisation of a new Vadodara Municipal Corporation (VMC) headquarters.

“This initiative is not merely about constructing a new building,” Mr. Babu says during a conversation with Indian Masterminds. “It represents a strategic reform in how the city is governed—simplifying civic interactions, strengthening institutional capacity, and creating a governance system that meets the expectations of a rapidly growing city.”

A NEW HEADQUARTERS, A NEW GOVERNANCE CULTURE

For nearly two decades, the idea of a new VMC headquarters lingered on paper. This year’s budget finally moves it forward decisively. The proposed headquarters is envisioned as a single-window, integrated civic hub—bringing together departments currently scattered across the city.

“When municipal offices function from dispersed locations, citizens are compelled to navigate multiple touchpoints,” Babu explains. “By consolidating them, we reduce turnaround time, enhance transparency, and offer a predictable service experience.”

The move is as much about citizen convenience as it is about administrative efficiency. Thousands of daily trips to different municipal offices add to congestion, particularly around the Khanderao Market area. A purpose-built campus with organised access, adequate parking, and multimodal integration is expected to reduce pressure on the city core.

Importantly, the shift will also allow the historic Khanderao building to be restored and preserved as a heritage structure rather than strained by intensive administrative use.

“Preserving our architectural legacy while transitioning to modern infrastructure reflects responsible governance,” he notes.

FROM FRAGMENTED PROJECTS TO SYSTEMIC TRANSFORMATION

Beyond the headquarters, the 2026–27 budget signals a broader shift—from isolated works to integrated urban systems aligned with the Viksit Bharat 2047 vision.

Babu identifies three structural changes at the heart of this transformation.

POLICY-DRIVEN URBAN GOVERNANCE

The budget introduces and operationalises 14 key municipal policies, covering areas such as parking, street vending, public health bye-laws, rainwater harvesting, urban greening, heritage conservation, Transfer of Development Rights (TDR), wastewater reuse, debt management, and municipal bonds.

“We are moving from ad-hoc decision-making to policy-led governance,” says Mr. Babu. “Clear rules create predictability—for citizens, investors, and administrators alike.”

This codified framework aims to ensure consistency, institutional accountability, and measurable on-ground outcomes.

INFRASTRUCTURE AS AN INTEGRATED URBAN SYSTEM

The second pillar reimagines infrastructure not as standalone projects but as interconnected systems.

The budget outlines new corridors, flyovers, and road networks to decongest critical junctions. Investments in water source augmentation, stormwater drainage strengthening, and wastewater reuse aim to build resilience against flooding and water stress.

But the transformation extends beyond roads and pipelines.

Model schools, 50 anganwadis, health centres, six fire stations, new sports complexes at Akota, Gotri, and Sayajipura, libraries, yoga centres, swimming pools, canal-front linear parks, lake rejuvenation projects, and iconic public spaces form part of a broader civic upgrade.

“Urban infrastructure must address mobility, health, education, recreation, and livelihoods together,” Mr. Babu emphasises. “Only then does development translate into quality of life.”

The inclusion of labour chowks, working women’s and youth hostels, and PMAY 2.0 housing initiatives signals attention to inclusivity and affordability.

CLIMATE RESILIENCE AND FINANCIAL SUSTAINABILITY

The third structural shift embeds sustainability and fiscal prudence into city planning.

The budget proposes 20 MW of solar energy generation to offset municipal power consumption, expansion of urban green cover from 17% to 21%, strengthened stormwater drainage, and water reuse initiatives projected to generate ₹50 crore in revenue.

Additionally, ₹200 crore in Blue Municipal Bonds and frameworks for municipal bonds more broadly aim to fund sustainable water infrastructure and long-term projects without compromising financial stability.

“Resilience and fiscal responsibility must go hand in hand,” Mr. Babu says. “We are building infrastructure that is climate-responsive and financially sustainable.”

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) and strategic monetisation of VMC plots are expected to strengthen the corporation’s fiscal base.

DATA-DRIVEN, FUTURE-READY GOVERNANCE

A key feature of the new headquarters and broader administrative reform is institutional strengthening through specialised cells—GIS, Quality Control, Vigilance, Animal Nuisance Control, Heritage, Energy Efficiency, Transportation, and Climate Action.

“Dedicated cells enable evidence-based planning and real-time monitoring,” Mr. Babu explains. “We are embedding data-driven decision-making into everyday governance.”

GIS-enabled systems, digital dashboards, and structured service-level agreements (SLAs) aim to make service delivery transparent and accountable. Citizens will increasingly access services online, with fewer physical visits and faster grievance redressal.

EVERYDAY LIFE, TRANSFORMED

For Vadodara’s residents, these reforms are not abstract policy shifts—they promise tangible improvements.

Shorter travel times due to better corridors and flyovers. More reliable water supply. Improved drainage during monsoons. Cleaner neighbourhoods supported by updated public health bye-laws. Expanded green spaces and canal-front parks for recreation. Enhanced emergency services with new fire stations. Accessible sports, cultural, and library facilities.

“Ultimately, citizens should experience governance as seamless and dependable,” Mr. Babu reflects. “The goal is a city where services are accessible, transparent, and aligned with people’s daily needs.”

Over the next five to ten years, the cumulative effect of these measures could redefine Vadodara—from a city balancing heritage and growth to one confidently stepping into a future of integrated systems and accountable governance.

As the 2013-batch IAS officer charts this course, the symbolism is striking. A century-old civic landmark prepares for conservation, while a new institutional backbone rises—digitally enabled, climate-responsive, and citizen-centric.

In Arun Mahesh Babu’s blueprint, Vadodara is not merely expanding. It is reorganising itself—systematically, sustainably, and with a clear eye on 2047.