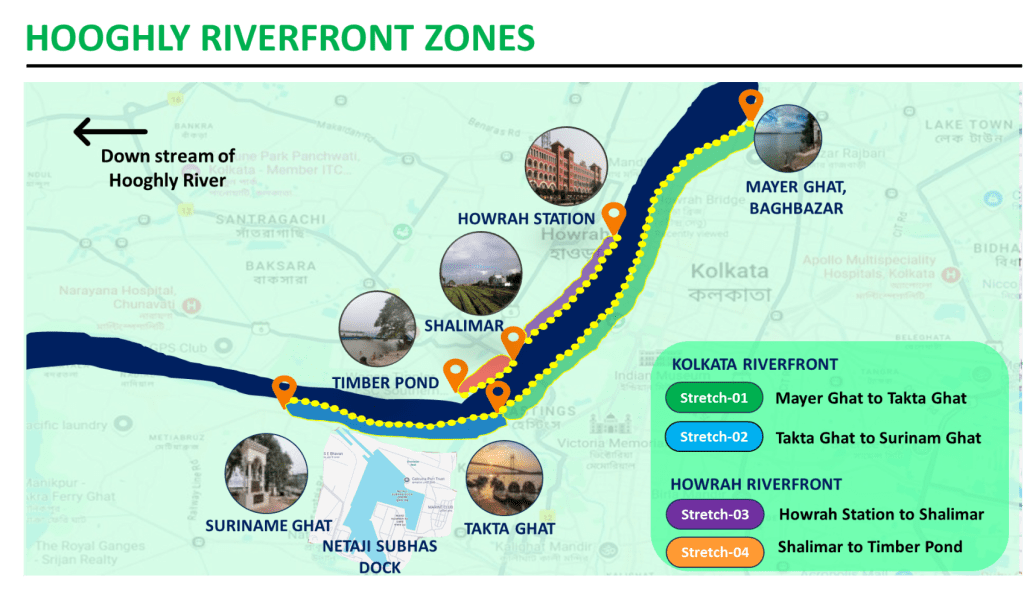

For centuries, Kolkata grew by facing the Hooghly. Trade ships anchored its economy, ghats anchored its spirit, and dockyards shaped its urban form. Yet over time, the city turned its back on the river that created it. The waterfront narrowed into utility spaces, encroachments crept in, and access faded from public life.

When IRS officer Samrat Rahi took charge as Deputy Chairperson of the Kolkata Dock System (KDS) at the Syama Prasad Mookerjee Port, he encountered not just a riverfront in disrepair, but a city that had stopped imagining the Hooghly as part of its future.

What followed was not a sudden overhaul, but a steady reframing of how the river, land, heritage, and governance could work together.

SEEING POSSIBILITY WHERE OTHERS SAW CONSTRAINTS

Rahi’s approach was shaped by exposure beyond India. Shortly before assuming charge, he had closely observed riverfront development models in London and studied narratives from European cities and Singapore, places where rivers had been reclaimed not as decoration, but as working civic spaces.

“When you see how other cities treat their rivers, you realise the issue here is not lack of potential. It’s about clarity of purpose,” he shared in an exclusive conversation with Indian Masterminds.

Eastern India, he knew, came with its own challenges, such as encroachment, cautious investors, limited lease periods, and long-standing unauthorised occupation of premium land. These factors had historically discouraged private participation and delayed redevelopment.

Instead of viewing these as deal-breakers, Rahi chose to work within them.

“If land use is clearly defined, people respond,” he explains. “If everything is left open-ended, nobody comes forward.”

CHANGING HOW THE PORT THINKS

Under Rahi’s stewardship, the Kolkata Dock System began looking beyond its traditional role of managing cargo and navigation. The river was reimagined as urban infrastructure, capable of supporting public life, tourism, culture, and local economies.

The shift was subtle but decisive. Projects were no longer conceived as isolated beautification works. They were tied to embankment safety, erosion control, environmental safeguards, and continuity of access.

Nearly 30 kilometres of riverbank on both sides of the Hooghly were mapped for phased development, with structural stability placed before visual change.

“You cannot build promenades on weak embankments,” Rahi notes. “If the foundation isn’t right, everything else is temporary.”

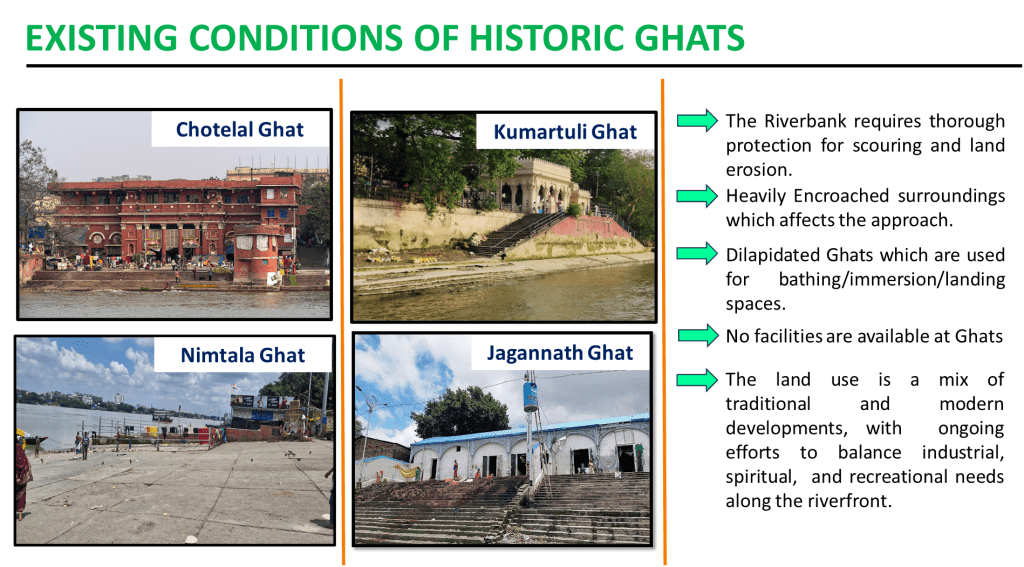

GHATS, WAREHOUSES, AND THE QUESTION OF USE

One of the most sensitive aspects of the riverfront push has been heritage. For Rahi, Kolkata’s ghats are not museum pieces but active spaces, used for rituals, labour, craft, and daily life.

Their revival has been planned through structured CSR partnerships with public sector units, corporates, and institutions, ensuring restoration without stripping away character.

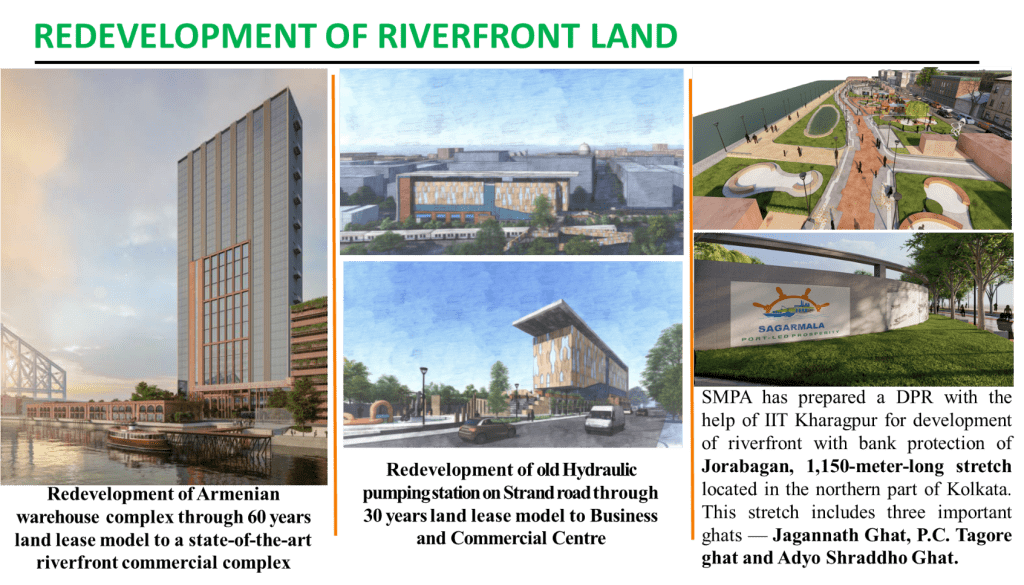

The same philosophy guided decisions around obsolete port warehouses. About 11 acres of non-operational estates were identified for adaptive reuse, retaining industrial identity while opening doors to cafés, cultural venues, sports and recreational spaces, banquet facilities, and commercial activity.

“These are premium properties that have been locked into old patterns for decades,” Rahi says. “Changing their purpose changes the city’s pressure points.”

The intent is also economic: to decongest areas like Burrabazar and distribute commercial activity along the river.

TAKING CALCULATED RISKS WITH INVESTMENT

A core part of Rahi’s work has been shifting the riverfront conversation from grant dependency to revenue-generating ecosystems. By combining government funding, long-term leasing, and private participation, the aim is to create projects that sustain themselves.

He acknowledges the risk involved.

“Once you reserve land for a defined purpose like a hotel, storage, or for leisure, the answer becomes yes or no,” he says. “But without taking that step, nothing moves.”

The approach has already begun attracting interest, gradually changing perceptions about Kolkata as an investment destination.

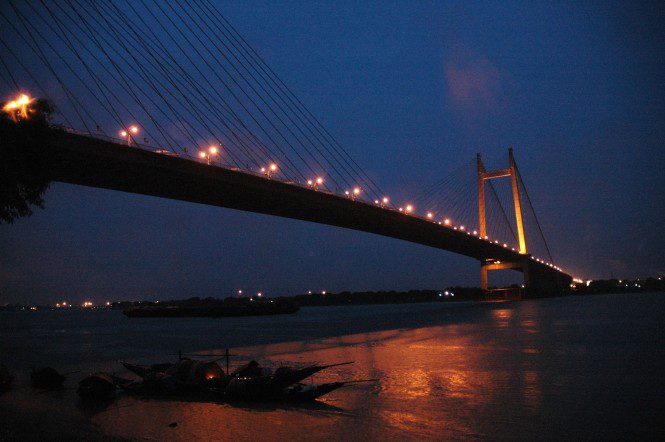

HOWRAH BRIDGE AND THE LANGUAGE OF THE CITY

Among the most visible outcomes of this thinking is the plan to transform Howrah Bridge through global-standard illumination, thematic lighting, and music projections on national and cultural occasions.

To Rahi, these are not cosmetic gestures.

“Cities respond to mood,” he explained to Indian Masterminds. “Light, sound, and access tell people that a space belongs to them.”

With programmable systems capable of multiple themes across the year, the bridge is being repositioned as a civic landmark that speaks to the present while carrying its history forward.

LEADERSHIP WITHOUT OWNERSHIP

Despite the scale of work, Rahi is clear that the riverfront is not a personal project.

Yet he also recognises the role of the person occupying the chair. Administrative exposure, global awareness, and willingness to rethink routine processes shape how policies are interpreted on the ground.

“The same system can produce very different outcomes,” he reflects. “It depends on how you look at it.”

A CITY LEARNING TO FACE ITS RIVER AGAIN

With over twenty projects planned in the coming five years, Kolkata stands at a moment where imagination must be matched with regulation and balance, with ecology, culture, and access moving together.

In reclaiming the Hooghly, Rahi’s work is quietly guiding Kolkata back to an old truth, that the city grows best when it looks toward its river, not away from it.