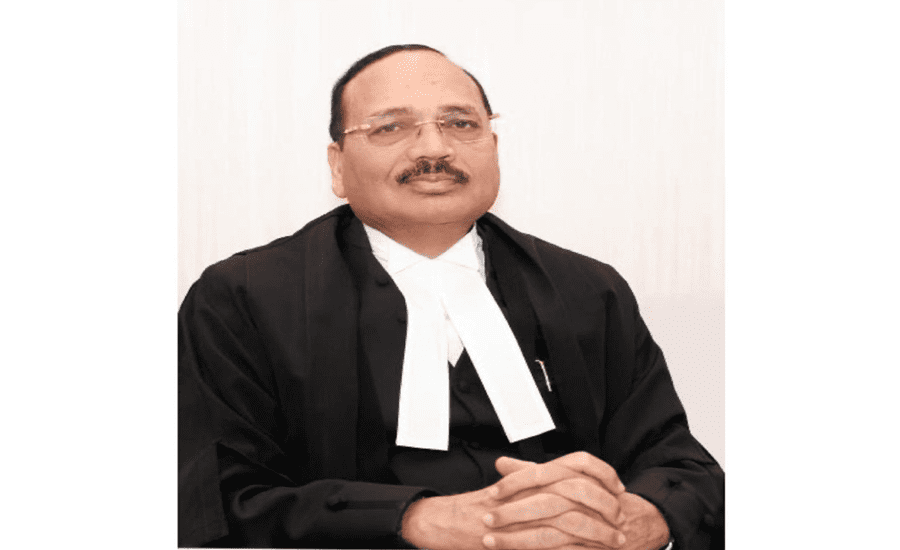

New Delhi: A Bench of the Supreme Court of India, led by CJI Surya Kant and Justice Joymalya Bagchi, made a compelling suggestion that matters involving organised, professional and hardcore criminals registered under central laws should be investigated by the National Investigation Agency (NIA) — India’s premier counter-terrorism and national security investigative body.

The apex court’s recommendation came amid concerns that hardened offenders exploit jurisdictional overlaps and procedural complexities in the criminal justice system, potentially resulting in delayed justice and increased risk to public safety.

Background of Organised Crime and Judicial Concern

India’s criminal justice system is structured around a combination of state police forces, central agencies, and a layered judiciary. When serious offences — particularly those involving organised crime, major syndicates, interstate gangs or terror-linked activities — occur, law enforcement agencies sometimes face challenges due to jurisdictional constraints and procedural delays.

The NIA, established under the National Investigation Agency Act, 2008, has the authority to investigate specific scheduled offences across state boundaries and take over probes where multiple FIRs are lodged in different states.

Traditionally, its mandate has focused on terrorism and offences affecting national security. But the Supreme Court’s latest suggestion points toward expanding NIA’s role to handle complex organised crime cases involving “hardcore criminals”.

Bench Observation: Why Hardcore Criminal Cases Need a Central Focus

During hearings related to the pendency of gangster-linked and organised crime trials in the National Capital Region (NCR), the Supreme Court pointed out that offenders often move across states to evade arrest, lead prolonged trials, and exploit jurisdictional uncertainties.

This, the Bench observed, ultimately benefits hardened criminals, which is neither in the interest of the criminal justice system nor public safety.

The Bench acknowledged that existing laws and investigative structures are not always sufficient to ensure swift, coordinated action against professional criminal networks — particularly where multiple FIRs across different states create legal and logistical bottlenecks.

CJI Surya Kant highlighted that such societal threats demand “serious consideration” of legislative and systemic solutions that better utilise existing legal architecture.

The Proposal: NIA’s Potential Expanded Role

In framing its suggestion, the Supreme Court signalled that the NIA Act’s supervening power could be leveraged to consolidate investigations in cases of organised crime involving “hardcore criminals”, especially where multiple state FIRs exist. Justice Joymalya Bagchi underlined that under Section 6 of the NIA Act, the agency can take over investigations that cross state boundaries or involve serious offences affecting national stability or public order.

The Bench expressed that a scenario where state boundaries or procedural overlaps allow offenders to slip through the judicial process is unacceptable. By allowing the NIA to handle such cases, the Bench argued, law enforcement could be more unified, systematic and effective.

Judicial Infrastructure and Legislative Considerations

The Supreme Court also emphasised that addressing organised crime effectively means not only expanding investigative responsibility but also ensuring adequate judicial infrastructure to dispose of such cases promptly.

One of the focal points of the hearing was the need for dedicated courts that can expedite trials under central laws such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), the NIA Act, and other relevant statutes.

During the hearing, it was noted that multiple trial courts in the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi and the broader NCR region are already being readied to hear such cases, but there remains a need for a comprehensive framework that ensures consistent and rapid judicial action.

Further, legal officers informed the Bench that the Centre is considering the setup of special courts dedicated to NIA cases in each state and Union Territory — including additional judicial infrastructure where the caseload exceeds thresholds — to avoid backlog and delays in trials involving terrorism, organised crime, or hardcore criminal activity.